By Hand or by Machine? The Evolution of a Low-Tech Answer for the Most Difficult Cataract Cases

$5 surgeries, clockwork efficiency, and the bidirectional transfer of skills – what our UCSF ophthalmologists learned from Nepalese colleagues.

The day had begun as it usually did.

There was eye clinic in the morning, cataract surgeries till the afternoon, and now a few hours of “wet lab,” where UCSF ophthalmologists Neeti Parikh, MD and Madeline Yung, MD hone their surgical skills on practice bovine eyeballs.

Only this time, they’re not in San Francisco.

Supported by the UCSF Faculty Learning and Development Fund, Parikh and Yung have a unique vision in mind: to train in the art of small incision cataract surgery (SICS) in one of the very places where it was pioneered – the world-renowned Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Prior to their trip, Parikh and Yung’s goals were three-fold: first, to learn SICS from the experts; second, to return home and train their colleagues and residents in this technique; and third, to introduce its use for San Francisco patients with advanced cataracts.

“We were initially flabbergasted by some of the things that were done as part of routine practice at the [Tilganga] Eye Institute, but it works… It’s important to take the mind of a learner, to stay humble, and to really try to view everyone that you meet as someone that you could potentially learn something interesting and lasting from.”

Yet even their first day in Nepal made clear that there was much more to learn, experience, teach, and grapple with.

“The way that things are done in the U.S. isn’t necessarily the gold standard,” says Yung. “We were initially flabbergasted by some of the things that were done as part of routine practice at the [Tilganga] Eye Institute, but it works… It’s important to take the mind of a learner, to stay humble, and to really try to view everyone that you meet as someone that you could potentially learn something interesting and lasting from.”

So, what did we learn?

“Technologically advanced” is not always superior

About half of all Americans aged 75 or older will experience the burden of cataracts – a clouding in the lens of the eye that can lead to blindness.

And when it comes to treating cataracts, all American ophthalmologists practice phacoemulsification surgery, or “phaco,” while a much smaller number practice (and are comfortable) with SICS. In the U.S., phaco is gold standard for cataract removal, and relies heavily on ultrasonic machines to break up and extract the cataract. In SICS, the surgeon excises the entire cataract by hand, using a blade the width of a sesame seed and a wire loop the size of a cuff link.

At first glance, the “technologically advanced” phaco may seem like the superior choice. Yet SICS offers several advantages:

Yung and Parikh discuss the differences between two popular cataract procedures: phacoemuslfication, which uses ultrasonic energy delivered through a very small incision to break up the cataract; and small incision cataract surgery, which involves a larger incision and removal of the lens but requires less expensive equipment.

(1) Reaching more patients in a safer way

Phaco is suitable for patients with mild to moderate cataract, who present early in the course of the disease with blurry, clouded, or dim vision. Think of these cataracts like a milky screen: “soft” enough to zap and suction using phaco.

Now, consider patients without insurance, access, or resources. These patients are often forced to tolerate their cataracts to the point of near-blindness before seeking care. Thus, they present with dense, advanced cataract, less milky screen and more… well, hard brown rock.

For these patients, phaco may still be an option, but SICS is potentially safer.

“In phaco,” Yung explains, “the use of excessive ultrasonic energy risks damage to the eye’s corneal endothelial cells.” These cells are crucial to pumping water out of the eye to prevent swelling. Therefore, damaging these cells could lead to corneal swelling, which may later necessitate a corneal transplant.

The denser the cataract, the greater amount of ultrasonic energy is required to treat it. Thus, compared to patients with mild to moderate cataract, patients with advanced cataract are at increased risk of corneal damage and adverse outcomes.

“It’s just much easier to deliver the dense lens [as a] whole as opposed to trying to break up something that’s rock hard into pieces,” says Parikh.

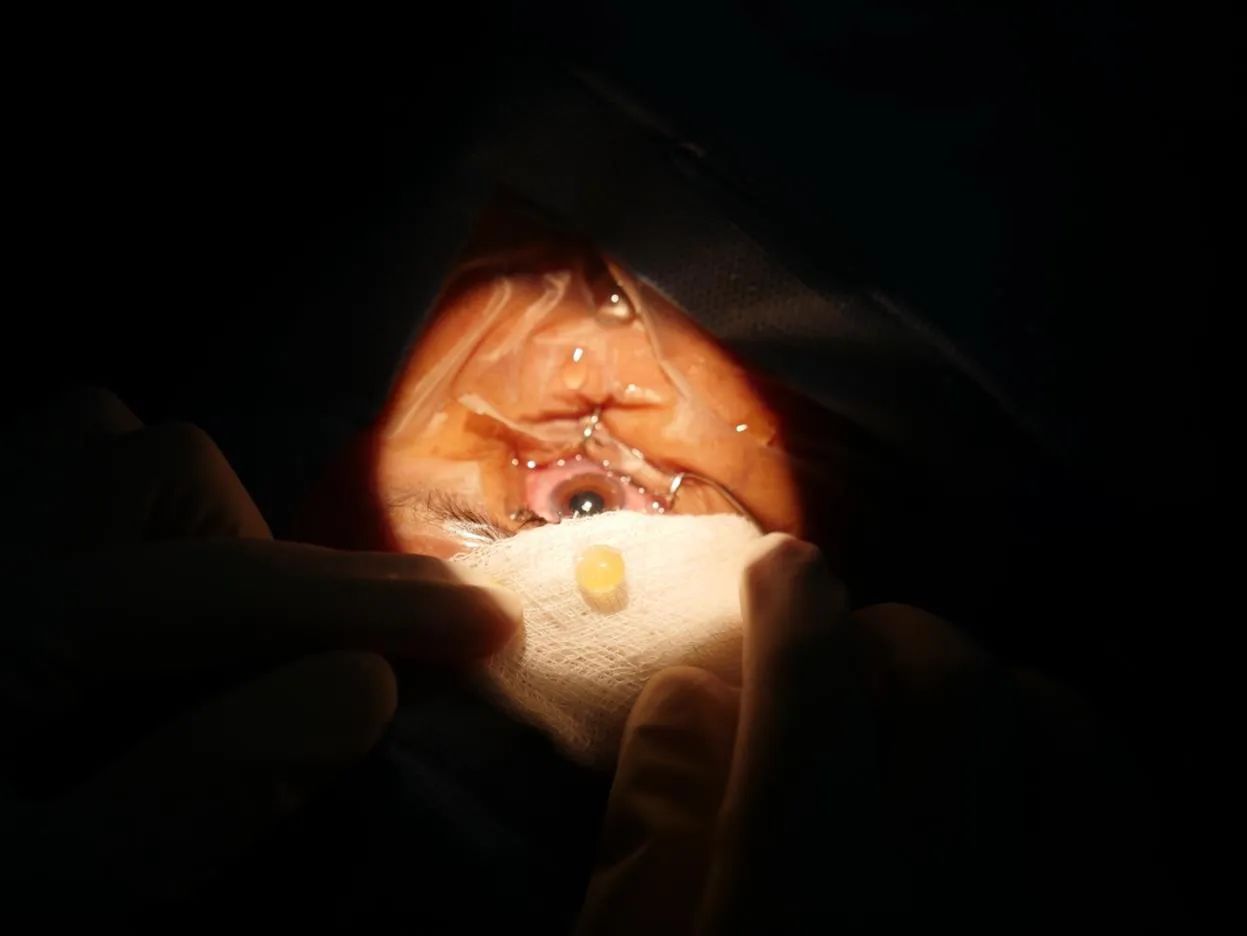

A cataract is removed as a whole during the SICS procedure.

A cataract is removed as a whole during the SICS procedure.

Consider also who is most likely to suffer from advanced cataract, and ironically be ineligible for surgical treatment in the U.S.: patients of lower socioeconomic status, who are disproportionately immigrants, racial or ethnic minorities, or both.

Without alternatives to phaco, these well-known disparities in cataract burden may continue to worsen. But the implementation of SICS – six times cheaper than phaco – may be the first step in reversing this trend.

Therein lies SICS’s second advantage.

(2) Lower costs

A 2007 study found that for a hospital in Pune, India, the average cost of a phaco procedure was equivalent to $42.10, compared to $15.34 for SICS. These costs included fixed facility costs and the costs for the phaco machine, its maintenance, and replenishment of parts. When fixed facility costs are removed from consideration, SICS costs about $5.00. Without a reliance on technology or machines, SICS is the superior choice in resource-strapped settings.

But what about the cost to patients?

“It’s usually about $100,” says Saksham Tamang, MD, a third-year resident at Tilganga. “But for patients who can’t afford the full price, their costs can be subsidized or fully covered by funds from the Tej Kohli & Ruit Foundation.”

(3) Equivalent outcomes

Finally, phaco and SICS result in similar visual outcomes, with little difference in visual acuity or post-operative complications following the surgery. SICS is also significantly faster than phaco, averaging 10.8 minutes compared to phaco’s 13.2 minutes. Although seemingly insignificant at first glance, the cumulative effects of this difference have led SICS to become the preferred method of cataract extraction in areas with high-volume needs.

Adding to your arsenal of tools

Hours of training accordion into the instant Yung sets scalpel to sclera.

To her left, a chessboard of nurses, scrub techs, and trainees stand in rapt attention. To her right, her SICS mentor – Tilganga- and Stanford-trained Shyam Vyas, MD – gives an encouraging nod.

Later, Yung would tell me that there was nothing quite like performing surgery. “The first time you operate on a patient,” she says, “it’s like an adrenaline rush. You’ve spent so long training and practicing that when the real thing comes along, you know you’re ready.”

Yung (left) and her SICS mentor, Shyam Vyas, MD, prepare for their next surgery.

Yung (left) and her SICS mentor, Shyam Vyas, MD, prepare for their next surgery.

And ready they are. Under the tutelage Vyas and other Tilganga mentors – including Keepa Vaidya, MD; Anu Manandhar, MBBS, MD; and Tilganga CEO Reeta Gurung, MSc, MD – Yung and Parikh spend each day observing, deconstructing, and practicing their SICS maneuvers.

“Surgery is difficult to learn without an in-person mentor,” says Yung. “When you observe the masters, you should be critically analyzing each step [of the surgery]. That’s why at the end of every operating day, Dr. Parikh and I immediately and thoroughly discuss what we learned. You may know the theory behind it all, but that doesn’t mean you know the practice.”

Madeline Yung, MD (left), and Neeti Parikh, MD, outside the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Madeline Yung, MD (left), and Neeti Parikh, MD, outside the Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology in Kathmandu, Nepal.

In the wet lab, Tilganga CEO Reeta Gurung, MSc, MD (left), trains Parikh in SICS on a practice eye.

In the wet lab, Tilganga CEO Reeta Gurung, MSc, MD (left), trains Parikh in SICS on a practice eye.

In the operating theater, Parikh puts her training to use to perform SICS on a Tilganga patient.

In the operating theater, Parikh puts her training to use to perform SICS on a Tilganga patient.

Parikh and Yung review each step of SICS after a busy day in the operating theater.

Parikh and Yung review each step of SICS after a busy day in the operating theater.

Observing operating techniques from over the surgeon’s shoulder offers a wider field of view.

Observing operating techniques from over the surgeon’s shoulder offers a wider field of view.

Most important, Yung notes, is the practical experience of doing a live surgery under expert supervision – which is not feasible to do remotely. SICS – or any surgery for that matter – cannot be learned from Zoom, a textbook, or video alone. For example, while a video recording may capture each step of a cataract surgery, it cannot capture three-dimensional depth on a two- dimensional screen. In a procedure where every millimeter counts, depth is invaluable.

Furthermore, most videos of cataract surgery show only the eye and the tip of the surgeon’s instrument; anything beyond the frame is lost to the viewer’s imagination. In-person training, on the other hand, offers a wider field of view.

“I actually like observing the surgery from over the surgeon’s shoulder,” Yung says. “You can see every micromovement of their fingers and how their hands move in space.”

And when it comes to bringing these lessons home, Parikh and Yung emphasize the importance of “adding to your arsenal of tools” to become more sophisticated surgeons.

“I’ve never had a patient [whose cataract] I couldn’t phaco,” says Yung. “When all you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything like a nail. But if you have many different tools, you can be much more nuanced and detailed in choosing the best technique.”

Adding to their arsenal, Parikh and Yung hope, will allow them and their UCSF colleagues to provide safer, more tailored care to cataract patients throughout San Francisco.

Crossing continents: A bidirectional transfer of skills and expertise

But global health work is a two-way street, and Parikh, Yung, and the leadership of Tilganga recognize the importance of sharing what they can to the benefit of others.

“We are the experts on how to work in the worst conditions,” says Nabin Kumar Rai, Tilganga’s Director of Programs. “How to reach our communities, and how to make our workforce more efficient, are the main objectives.”

For Rai, these objectives are met through “innovative modalities”: tele-health, community-based eye centers with screening events, and mobile operating theaters. The establishment of telehealth and local eye centers in isolated rural communities has saved hundreds of patients the expensive trek to Kathmandu. The use of mobile operating theaters – which transport surgeons, staff, and supplies to these communities – also enables patients to undergo cataract surgery without ever leaving their homes. And, Rai adds, by training community-based doctors, nurses, and staff to screen for common eye diseases, patients can receive care where they are.

“We are ready to share our expertise,” says Rai. “We have something. The developed community have something. So, we are sharing the best innovative modalities [with each other].”

Rai and Chloe Sales, MS3, talk about the importance of sharing knowledge.

For Tamang, one of the greatest differences between Nepalese and American ophthalmology is residency training. In the U.S., ophthalmology residents train in phaco during all four years of their residency. In Nepal, residents undergo phaco training only if they pursue additional training after residency – and even then, phaco training lasts only six months.

Recognizing this difference as an opportunity to give back, Yung and Parikh offered to train Tilganga residents in phaco, just as their own mentors had trained them in SICS. Thus, Yung and Parikh hosted training sessions in the wet lab, where they coached Tamang and other residents through phaco, suturing, and other surgical techniques on practice eyes.

“They were really kind enough to help me out in the wet lab with the phaco training,” says Tamang. “We’re really thankful.”

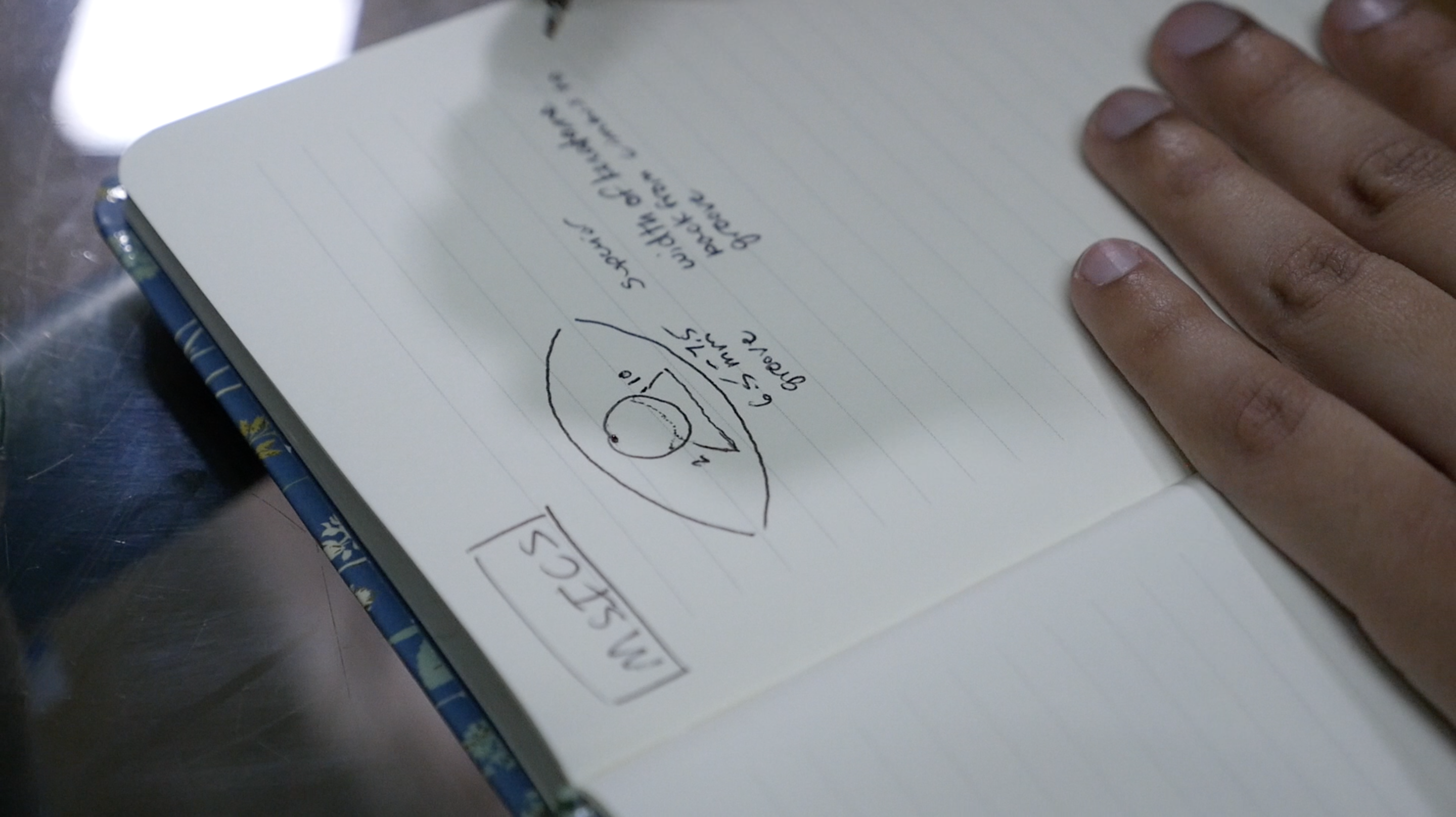

Outside the operating theater, Tamang (left) uses his notebook to demonstrate SICS technique to Parikh (middle) and Yung.

Outside the operating theater, Tamang (left) uses his notebook to demonstrate SICS technique to Parikh (middle) and Yung.

“When you go somewhere,” says Parikh, “you always want to try to leave something behind. On a trip like this, where you’re the trainee, it’s a little bit difficult, but what am I giving back to them? What kind of lasting effect am I going to have?”

For Parikh and Yung, the answers lie in continuing to share knowledge with Tilganga residents, even after returning to San Francisco. In collaboration with Tilganga faculty, they hope to deliver live Zoom lectures on phaco and other surgical techniques at resident teaching.

This is the tenet of global health work: the bidirectional transfer of skills, expertise, and opinions between two communities that teach and learn from each other. Also known as “skills transfer,” this practice is crucial to the continuous improvement of health systems across the world.

“I learned so much from just speaking to people from different health systems and cultures,” says Parikh. “Surgery-wise, in the U.S., we have various rituals between each case. Everything has to be changed – all the drapes, the instrument sets, the floors are mopped – a lot of those things are not done here [at Tilganga].

In the wet lab, Yung (left) and Parikh (right) train Tilganga residents in phacoemulsification and suturing techniques.

In the wet lab, Yung (left) and Parikh (right) train Tilganga residents in phacoemulsification and suturing techniques.

At first, we were like, ‘What is going on?’ But… [Tilganga has] very low rates of endophthalmitis, which is the worst eye infection you can get after eye surgery. We also noticed that the two things that are proven to reduce rates of endophthalmitis – iodine prep and intracameral antibiotic – they do.

So, it’s not that they’re ignoring evidence-based studies. They’re just not doing a lot of things that [Americans] do because it may or may not evidence-based… It does make you think about things. OR waste is a huge deal in the U.S.”

For Yung, another surprise was patient flow at Tilganga.

“For example,” Yung says, “[Tilganga] patients would not have an IV, whereas all patients getting surgery, no matter how minor at UCSF, get an IV so they can receive pain medications, sedating medications. [Tilganga] patients are led to the operating table, walking on their own two feet, then laid down, with no systemic anesthesia.” (Notably, Tilganga patients receive local anesthesia to the eye only.)

“[Tilganga patients] stay more still than patients do in America,” Yung adds. “In the meantime, the next patient is waiting just outside the room… So, the patient flow is definitely very interesting, but it’s also pretty efficient.”

Whether these practices can (or even should) be integrated into the American health system is a separate debate, but for Yung and Parikh, even exposure to alternative hospital workflows raises new possibilities for patient care in San Francisco, and possibly beyond.

“I don’t know that I’m asking for a change in things,” says Parikh, “but it does make you think about things that we could change.

Getting involved: Go with the flow, acknowledge challenges, and contribute to sustainable partnerships

So where does that leave you?

For those who wish to become involved in global health work – ophthalmology or otherwise – Yung and Parikh suggest adopting the right mindset first.

“Have a ‘go with the flow’ attitude,” says Parikh, “If you go with the flow, then you’ll actually just take advantage of whatever comes your way.”

For Yung, it is also crucial to cultivate awareness of and address the rising controversies surrounding global health. “Just because you feel good about yourself,” she asks, “does anybody else?”

Critics of global health and missionary work point to potential harms to the host country, such as pervasive undertones of colonial saviorism – a phenomenon in which wealthy Western foreigners simultaneously “save” the poor. Others criticize the transient nature of so-called “voluntourism,” which may serve the goals of the “voluntourist” rather than the long-term needs of the intended beneficiaries and their communities.

Reassuringly, global health experts recognize these challenges and are moving toward establishing sustainable partnerships led by local organizations in the host country. Tilganga, for example, has long-established partnerships with the Himalayan Cataract Project in Ethiopia. And for an institution like Tilganga, training international healthcare workers only serves to strengthen that sustainability.

“I got training from the U.S., came back [to Nepal], and launched so many things here,” says Srijana Adhikari, MD, Tilganga’s Head of Pediatric Ophthalmology. “We have fellows from Ethiopia, Canada, Mexico, and Indonesia, and so many other countries who come here to learn from us.” Adhikari has also traveled to these countries to teach, creating sustainable partnership programs to disseminate knowledge across the globe.

Chloe and Paul Brandfonbrener, MS2, hosts of The Spark podcast, reflect on lessons learned.

The intricacies of global health – its benefits, challenges, and controversies – are far more nuanced and complex than can be addressed in a single training program. And traveling to a foreign country to undergo further training may not even be a possibility for all surgeons. But even for non-medical members of the community, supporting existing institutions and partnerships carries great positive potential.

“We need a lot of help,” says Adhikari. “[Patients] have a lot of costs, but what I feel is that the stress they go through, the emotions that they go through, is far more than the money that is required. At least if we can help them from the monetary side, then that would be really good for them.”

Just the beginning

At the SICS Certificate Ceremony. From left: Shyam Vyas, MD; Parikh; Yung; Tilganga PR Officer Dinesh Pokharel; Keepa Vaidya, MD; and Tilganga Sr. PR Officer Sunita KC

At the SICS Certificate Ceremony. From left: Shyam Vyas, MD; Parikh; Yung; Tilganga PR Officer Dinesh Pokharel; Keepa Vaidya, MD; and Tilganga Sr. PR Officer Sunita KC

Weeks of intensive training come to a close, and at the SICS Certificate Ceremony, Tilganga mentors Vyas and Vaidya joke that despite their short training period, Parikh and Yung already demonstrate skilled mastery of SICS.

“I don’t think I need to teach you anything,” Vyas jokes. “You already know everything!”

“We wish you stayed longer,” says Vaidya. “This is just the beginning.”

Indeed, Parikh and Yung’s time with Tilganga has not ended with their return to the U.S. Even on the plane ride back to San Francisco, they brainstorm which lectures and PowerPoints to deliver and share at Tilganga resident teaching; how they might be able to help Tilganga obtain additional training supplies; and how they will help their colleagues travel to Kathmandu to undergo similar surgical training.

“We learned a lot,” says Yung. “We learned from our mentors, the residents, the staff… We really appreciate that.”

“Overall, this has been an excellent, excellent experience,” says Parikh. “It met expectations and more… I’ve had a great time and I’m really grateful to Madeline [Yung] and to everyone at Tilganga.”

More from Nepal

In a special three-part miniseries of the UCSF School of Medicine's The Spark podcast, Chloe talks with Tilganga and UCSF faculty about ophthalmological procedures, the similarities and differences in surgical training in Nepal versus the US, and the lessons we can learn from each other.